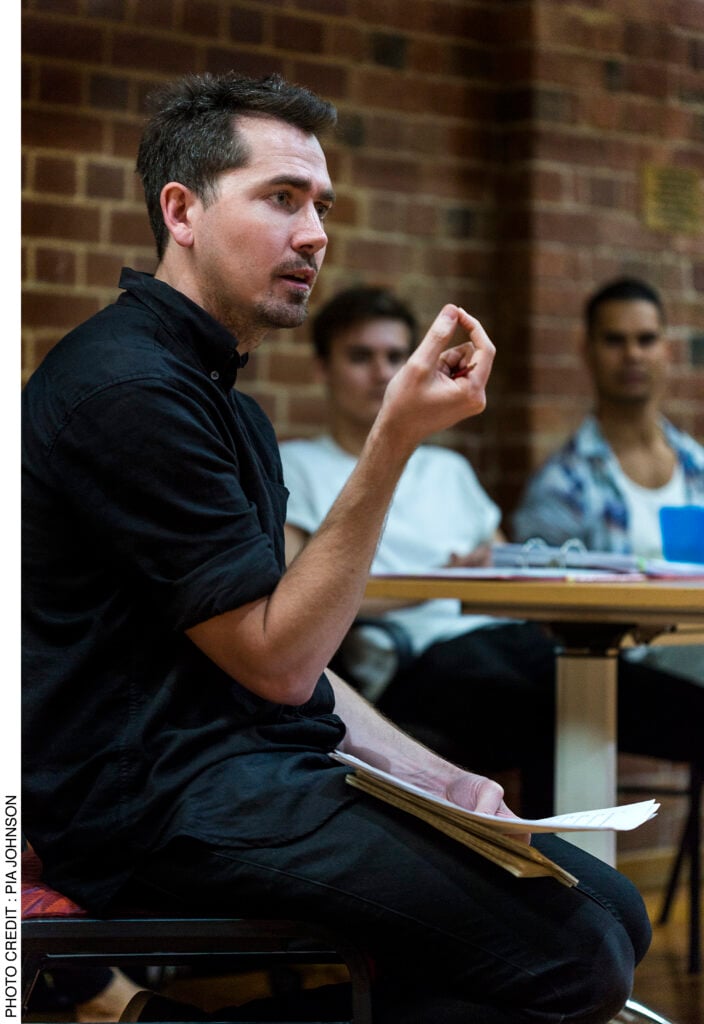

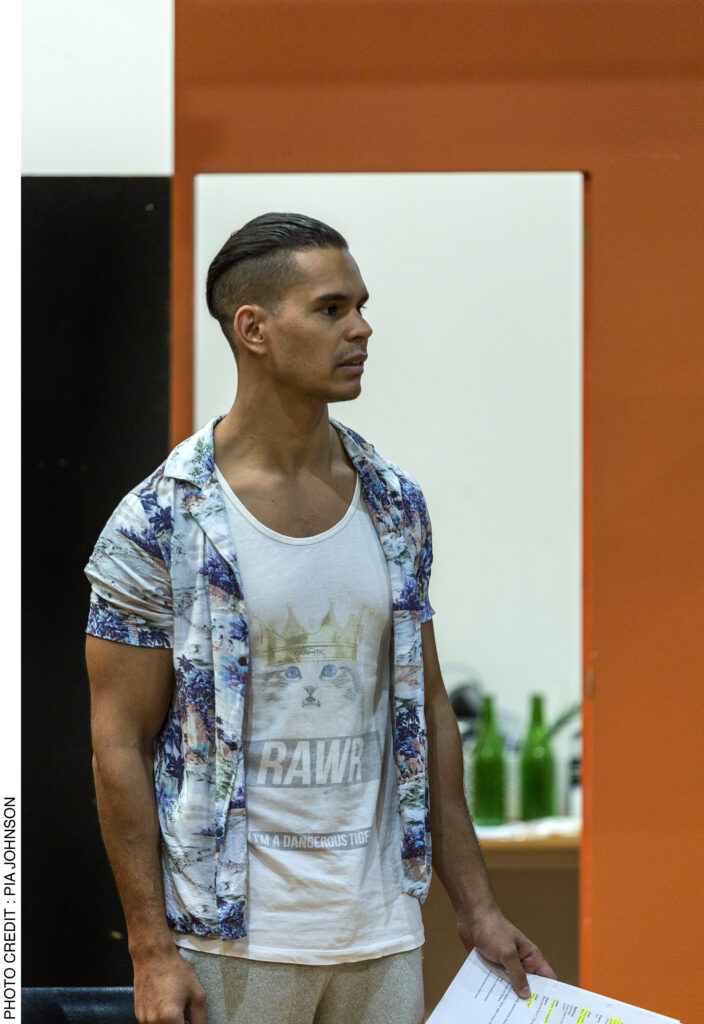

Malthouse Theatre’s Youth and Education Manager Vanessa O’Neill met with their Artistic Director Matthew Lutton to discuss the Malthouse Theatre and Belvoir production of Bliss.

Why are you interested in staging Peter Carey’s novel Bliss?

I am interested in staging Australian classics that offer a theatrical challenge, and that critique and reveal who we are today. At a time when men are needing to re-evaluate their place in the world, it is fascinating to interrogate how Harry Joy experiences a similar awakening and attempts to negotiate what it means to no longer be at the centre of power. I am also interested in telling an Australian classic that has great humour and is wildly eccentric, and that is the terrain of Peter Carey.

Carey’s award-winning novel was written in 1981. What are the key themes of Bliss and how do they speak to audiences in 2018?

There are many, many themes in Bliss. It is a story about a lot of different diseases: capitalism, Australia’s cultural cringe, Americanism, cancer, patriarchy, drugs. These diseases were growing the 1980s, and many are now in full flight.

It is a story about the hope for change and trying to find ‘cures’ for these diseases among clashing social ideologies. It is also a story about what it means to try and ‘be good,’ to strive for goodness, if ‘goodness’ even exists.

It is also a story about developing culture, and the need for stories. We need stories in Australia to help clarify what is happening around us, and many of these characters don’t have Australian stories to help guide them, so they invent them.

How conscious will audiences be of the early 1980s setting throughout this production?

The production is clearly set in the 1980s, even though it is told with a 2018 lens. It will be costumed in 1980s clothing and the aesthetic of the stage references will be from the 1980s, but the commentary throughout the script is from a 2018 perspective.

Bliss has already been adapted into a film and an opera. What does a theatrical adaptation offer (as distinct from the other forms)?

Direct storytelling with the audience is what theatre can offer. The characters in this adaptation can speak directly to the audience, so the audience can be involved in the many stories within stories.

Harry’s theory that everyone in the world (or ‘Hell’ as he sees it) is an ‘actor,’ also acquires new resonances when adapted for the stage. The actor playing Harry is constantly able to step out of the show and question whether the theatre and people onstage with him are ‘real’ or not.

A key premise of the story is that after Harry Joy ‘dies,’ he comes to the belief that he has woken up in ‘Hell’. How will Harry’s perception of ‘Hell’ be created throughout this production?

The key thing about Harry’s experience of ‘Hell’ is that he is now aware of what has always been around him—he just never paid it enough attention. Hell is therefore Harry’s increasing paranoia as he recognises the prevalence of ‘sins’ and ‘diseases’ around him, and his complicity in them.

There is also great level of humour in the way Harry navigates Hell. In this production, we will give him a dictaphone, which allows him to constantly record his conversations, and share them with the audience.

The staging of the production is about Hell being the same ideas seen from a different point of view. Each of the five acts can be considered as another layer of hell (like Dante’s Inferno), where the same stage elements are re-arranged, duplicated, enlarged or shrunk. A wooden room, a glasshouse that can move and make images appear and disappear, lots of chairs, lots of wine bottles, all these elements help to create our many layers of Hell.

Peter Carey himself worked in advertising in the late 1970s in Australia and his first novel is a very savage critique of the advertising industry. How will this critique be explored in this production?

It is explored mainly through the character of Bettina (Harry’s wife), and the theme of cancer. Bettina sees the beauty or art in advertising, and the safety it can bring you, but living with this view also brings about her death. There is also a very clear motif throughout that advertising is about alternative facts and truth is never a priority. All the products mentioned throughout Bliss cause cancer, and every ‘ad’ conveniently prefers not to mention this.

The creative team are almost the same team that you worked with on Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man. What are some of the advantages of working with the same creative team on a range of productions?

It means as a team you can take risks. Bliss is by far the largest, most complicated collaboration this team has undertaken. It is complicated because it is a sprawling story with many layers, and we need a lot of theatrical solutions to keep the production inventive. Working with a team that already has a strong working relationship means we can go much deeper into our artistic conversations and have a shared vocabulary.

What are some of the key choices that you have made regarding the set, lighting and sound design of this production?

For the set design, we have decided to create a storytelling space, a room with a 1980s aesthetic. Then, inside this room is another room—a glasshouse. This becomes our magic portal into new layers of Hell: our interrogation room, our capitalistic beacon, a glass ceiling that needs to be smashed, a birthing chamber, a paradise. Lighting this glass structure onstage (that also rotates) will be an enormous lighting challenge.

The sound design will also be a challenge, as it needs to help the production shift location and atmosphere constantly. One thing that is unique in Carey’s novel, is that he doesn’t reference any pop culture. No music, fashion or artists are mentioned. We have therefore decided not to use any 1980s music, but instead will incorporate many of the TV and radio jingles that Peter Carey himself wrote when he was in advertising. This will create an urban soundscape that is the opposite to the beauty and serenity of the buzzing bees and nature that Harry encounters in the last act.

Could you tell us about the range of theatrical styles that this production will make use of?

The production will make use of an eclectic range of theatrical styles. The entire show has a level of satire, but then it breaks out into direct address through storytelling, as well as moments of choral narration, and even a dance routine.

The work is also one of magic realism. The world Harry sees around him is a real world where strange and surreal events occur: an elephant sits on his car, a colleague steals his identity, he flies over his own body. The production therefore requires a theatrical language that can be both real and surreal simultaneously. The story is quite urban, but that does not mean it feels like a domestic drama, it is more like an urban epic or an urban odyssey.

Finally — do any of the characters find ‘bliss’ in this production? How does this manifest itself?

Some do, some don’t. Harry certainly finds a sort of bliss when he discovers a way to slow down, be helpful, patient and not take up so much space. He discovers a personal bliss that involves planting trees, to create beautiful honey 30 years into the future. He also finds love with Honey Barbara, and a way to tell truthful, beautiful stories, as opposed to advertising. But this bliss isn’t a utopia. This is not a romanticised state of bliss. It is Harry recognising that the world is Hell, but that he can find purpose within it.